Sudan: The Condor’s Flight over a Silenced Tragedy

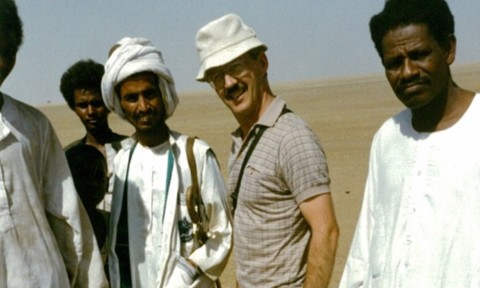

Roland Laneuville, pmé

In a gesture of suggestive imagination, a French actor depicted himself in fiction reincarnated as a condor. Borrowing this powerful bird as a metaphor for the perspective and moral height needed to observe the world, we embark on a flight to Sudan, a country experiencing one of the greatest humanitarian crises of our time, far, far away from Western attention.

Reader Warning: if you are looking for a light summer read, this is not the place. What follows is a journey through a territory devastated by war, a humanitarian catastrophe of colossal proportions that urgently needs to be known and understood.

A View from Above: An Expert Analysis

Our flight does not head first to Khartoum. It is better to pace the pain. We first soar to Nairobi, Kenya, to meet the expert voice of John Ashworth, a veteran observer of Sudanese realities. At our request, Ashworth outlined a stark panorama of the conflict tearing the country apart for more than two years:

"Let me give you some key points (the English phrase 'bullet points' seems appropriate for a war) that may help understand the situation:

• Sudan has a proven experience of nonviolent popular resistance (intifada). This overthrew military dictatorships in 1964, 1985, and 2019, but the military has always returned to power, as is happening now. I arrived in Sudan in 1986, just after the overthrow of one of these regimes, Nimeiry’s, and the establishment of a civilian government, which was overthrown two years later by Bashir, a military officer supported by the Muslim Brotherhood.

"Let me give you some key points (the English phrase 'bullet points' seems appropriate for a war) that may help understand the situation:

• Sudan has a proven experience of nonviolent popular resistance (intifada). This overthrew military dictatorships in 1964, 1985, and 2019, but the military has always returned to power, as is happening now. I arrived in Sudan in 1986, just after the overthrow of one of these regimes, Nimeiry’s, and the establishment of a civilian government, which was overthrown two years later by Bashir, a military officer supported by the Muslim Brotherhood.

• At one level, it is a conflict between two military factions: the SAF (official army) and the RSF (paramilitaries established as an alternative). But this is simplistic. In fact, the conflict has taken a deeply worrying ethnic dimension.

• It is crucial to understand how the army is entrenched in the country’s economy. Both factions derive funds from the gold mines they control, financing their arsenals. Both sides risk losing power and wealth, so the logic of war perpetuates.

• Currently, both sides still believe they can achieve military victory, so there are no serious peace negotiations.

• The establishment of two rival governments, dividing the country completely in two, is very negative. Both “governments” are military in nature, even if they claim otherwise.

• A dangerous side effect is the rise of regional and ethnic militias supporting one side or the other.

• This situation is widely considered the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophe, which says a lot given what is happening in Gaza, Ukraine, etc. The numbers, in real figures, are terrifying:

o 13,000,000 — number of displaced.

o 17,000,000 — number of out-of-school children.

o 150,000 — number of deaths.

• The conflict has alarming international dimensions, both regional (Libya, Chad, Kenya, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Sudan, etc.) and global (UAE, Wagner Group/Russia, etc.).

• Islamists, ousted from power in 2019, are regaining strength and influence.

• Nonviolent resistance continues, notably through Emergency Response Rooms (ERR), which have spontaneously arisen to provide humanitarian aid and some degree of organization and security to the population. This is a completely new model of resistance and aid, informal and decentralized, which the international community has failed to understand or recognize. In any future peace negotiations, ERR must have a strong voice, as they truly represent the people."

• It is crucial to understand how the army is entrenched in the country’s economy. Both factions derive funds from the gold mines they control, financing their arsenals. Both sides risk losing power and wealth, so the logic of war perpetuates.

• Currently, both sides still believe they can achieve military victory, so there are no serious peace negotiations.

• The establishment of two rival governments, dividing the country completely in two, is very negative. Both “governments” are military in nature, even if they claim otherwise.

• A dangerous side effect is the rise of regional and ethnic militias supporting one side or the other.

• This situation is widely considered the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophe, which says a lot given what is happening in Gaza, Ukraine, etc. The numbers, in real figures, are terrifying:

o 13,000,000 — number of displaced.

o 17,000,000 — number of out-of-school children.

o 150,000 — number of deaths.

• The conflict has alarming international dimensions, both regional (Libya, Chad, Kenya, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Sudan, etc.) and global (UAE, Wagner Group/Russia, etc.).

• Islamists, ousted from power in 2019, are regaining strength and influence.

• Nonviolent resistance continues, notably through Emergency Response Rooms (ERR), which have spontaneously arisen to provide humanitarian aid and some degree of organization and security to the population. This is a completely new model of resistance and aid, informal and decentralized, which the international community has failed to understand or recognize. In any future peace negotiations, ERR must have a strong voice, as they truly represent the people."

The Low Flight: Testimony from the Front Line

After this analysis, our condor, heart heavy with grim data, descends to Gedaref, a refuge city between Khartoum and Port Sudan, a route of exile toward Ethiopia. This area has been relatively spared by the war but has become a crucial shelter for fleeing displaced persons. There, a Sudanese priest, Father Quintino, works tirelessly. Through a miracle of perseverance and systems like Western Union, it has been possible to send him some aid. His testimony is direct and heartbreaking:

"In the cities of Gedaref, New Halfa, Kassala, Atbara, and Dongola, there is no electricity. The RSF continues shooting (using drones) at power facilities. People suffer from the lack of electricity and water. Imagine such human evil against other humans. In Khartoum, where I cannot go, the SAF continues massacring many South Sudanese suspected of having links with the RSF. Next week I will go to Galabat, at the border with Ethiopia, to serve my displaced people."

Khartoum: The Wounded City

Our condor then refuses to hover too long over the capital, Khartoum. The scene is too desolate. Archbishop Michael Didi has had to flee to Port Sudan. Cardinal Zubeir Wako is now in South Sudan. Places that were centers of community and faith, like the Catholic cathedral, lie damaged or turned into arms depots.

Journalistic investigations and reports confirm the situation:

Journalistic investigations and reports confirm the situation:

"Khartoum’s Catholic cathedral has suffered significant damage during the conflict. Photos show parts of the mission buildings covered in debris, walls marked by bullet or projectile impacts, and rooms blackened by smoke. The area around the cathedral has been severely affected by fighting."

A Silenced Tragedy: Echo in the Press

Exhausted, the condor returns, but brings evidence that, scarce as it is, Sudan’s voice sometimes breaks through. Le Devoir on July 14 dedicated an editorial to this crisis. Journalist Marie-Andrée Chouinard clearly exposes the paradox of its invisibility:

"Since April 2023, an estimated 13 million civilians have been displaced by the ongoing war, 30% of them to neighboring countries. About 17 million children are deprived of schooling, and nearly all (80%) hospitals in conflict areas have ceased functioning. Diseases like cholera, dengue, and malaria threaten the population.

Caught between the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Palestine conflict, Sudan’s civil war unfolds with almost no media coverage in the West. This raises complicated questions about what drives our sense of concern: given that atrocities in Sudan rival those witnessed in Israel, Ukraine, or Gaza, how does the international community choose when to denounce war crimes against the vulnerable?"

"Since April 2023, an estimated 13 million civilians have been displaced by the ongoing war, 30% of them to neighboring countries. About 17 million children are deprived of schooling, and nearly all (80%) hospitals in conflict areas have ceased functioning. Diseases like cholera, dengue, and malaria threaten the population.

Caught between the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Palestine conflict, Sudan’s civil war unfolds with almost no media coverage in the West. This raises complicated questions about what drives our sense of concern: given that atrocities in Sudan rival those witnessed in Israel, Ukraine, or Gaza, how does the international community choose when to denounce war crimes against the vulnerable?"

A Call to Conscience

This condor flight awakens the memory of a past hope. When our Society (the Quebec Foreign Mission Society) chose Sudan as a mission decades ago, it was thought: "Sudan? It is in the deepest pit; it can only improve!" History showed a tragic irony. Misfortunes have never ceased afflicting this beloved people. "Persecuted but not crushed," as St. Paul would say (II Corinthians 4:9).

To conclude, we make our own the words of Father Quintino, who from Sudanese soil cries out:

To conclude, we make our own the words of Father Quintino, who from Sudanese soil cries out:

"Let us continue to pray for peace in Sudan. The people are suffering too much!"